For months now, consumers in Europe have been startled when they walk into a supermarket and glance at the price label for ground beef. What used to be considered a relatively affordable staple for family dinners, hamburgers, or a weekday spaghetti Bolognese has turned into one of the most expensive items in the meat aisle. Dutch media recently picked up on the phenomenon when major retailers like Jumbo adjusted their prices sharply upwards, sparking predictable public debate about profiteering, inflation, and consumer substitution strategies such as mixing breadcrumbs or pork into beef mince.

Yet the story is neither local nor sudden. Beef is one of the most globalized food commodities in the world. Roughly half a million cattle are slaughtered in the Netherlands each year, a tiny figure compared to the more than 30 million slaughtered annually in the United States or nearly 40 million in Brazil. The domestic debate about Dutch supermarkets misses the point. The real drivers of beef price inflation lie in decades-long structural changes that affect global cattle herds, international trade flows, and consumer eating habits. To understand why beef mince has become “suddenly” expensive, one must look far beyond the chilled cabinets of European retailers and into the mechanics of global supply and demand.

A Decline Decades in the Making

It is tempting to assume that beef prices are rising because of a sudden shortage in global production. After all, scarcity is the oldest explanation for higher prices. But the data does not support that simple narrative. Brazil, the world’s largest exporter, increased its beef production by about fifteen percent between 2023 and 2024. The United States, while not growing, has kept production relatively stable. Global slaughter figures do not suggest a spectacular short-term drop.

What has been happening, however, is a gradual but relentless decline in the size of the U.S. cattle herd over the past four decades. In 1979, America’s herd numbered around 130 million animals. From that point, the curve bent downwards, partly because of shifting consumer demand toward chicken and pork, partly because of land-use pressures, and partly because cattle production cycles are inherently slow to adjust. By the early 2010s, the herd had shrunk to about 90–95 million. Today, it is closer to 87 million. That represents a reduction of roughly thirty-five percent, and it has profound implications for the resilience of the global beef supply.

Cattle cycles are long. A cow’s gestation lasts nine months, and it takes two years for an animal to reach slaughter weight or breeding maturity. Unlike poultry or swine, where producers can ramp up supply within months, the beef industry responds at a glacial pace. When herds decline, it can take five years or more before production rebounds meaningfully. That lack of elasticity makes the global beef market particularly vulnerable to shifts in demand.

When Demand Keeps Rising

While supply has stagnated or slowly declined, demand for beef has not. Quite the opposite. Rising incomes in Asia and Africa have brought millions of new consumers into the global beef market. Fast-food chains such as McDonald’s remain the single largest buyers of beef worldwide, driving structural demand for mince and burger patties. Even in Europe and North America, where overall meat consumption growth has slowed, the appetite for ground beef and processed beef products has steadily increased.

This creates a fundamental imbalance. Producers did not expand herds when cattle prices were low because returns on live animals were unattractive. But consumers—accustomed to accessible burgers, lasagnas, and meatballs—continued to demand more beef in precisely the form that puts the greatest strain on carcass utilization. The clash was inevitable: at some point, the world would run out of cheap beef trimmings.

The Hidden Economics of Trimmings

To truly grasp the current price surge, one must understand the concept of carcass valorization, sometimes called “the beef cut-out value.” A slaughtered animal is not simply a collection of steaks. Every carcass has a front quarter, hindquarter, and a range of primal cuts with varying market appeal. For most of the twentieth century, European consumers routinely purchased and cooked whole-muscle cuts: roasts, stewing beef, ribeye steaks. But over the last forty years, eating habits shifted decisively toward ground beef and convenience products.

The result has been a steady erosion in the relative value of traditional cuts. Where once the forequarter would be sold as braising steaks, chuck, or stew meat, it now almost entirely disappears into trimmings for mince and industrial hamburger production. Even the hindquarter, historically home to prized cuts such as topside or silverside, has increasingly been ground because trimmings commanded a higher price than these once-prestigious roasting joints.

When deboning beef carcasses, it became noticeable. In slaughterhouses in South America and Europe, many cuts of what is normally considered ‘premium’ meat were being thrown in with the batches destined for mince (trimmings). I asked why they didn’t keep the meat separate to sell it at a higher price.

The answer I got was that the demand for minced meat is so strong that it can hardly be met, and therefore cuts that are actually “too good” are also ground up—because even as mince they fetch a high price. Around the world, a massive “hamburgerization” has been underway for years. – Wouter Klootwijk

This development was slow and subtle. In the 2010s, trimmings sold for about €2.50–€2.70 per kilo, occasionally spiking to €4.00. Such prices were not enough to sustain profitable cattle production, especially when large parts of the carcass that once fetched premiums were reduced to commodity mince. Slaughterhouses adjusted what they paid farmers downward, since the overall carcass value declined. Farmers responded by breeding fewer animals, perpetuating the supply squeeze.

Now, with global demand for trimmings exploding, the balance has shifted violently. Every broker from Africa to Eastern Europe is chasing pallets of beef mince, pushing prices far beyond anything seen before. For processors, this is a nightmare: the mainstay of their product portfolio has become a premium commodity, while consumer willingness to pay is limited. For farmers, higher cattle prices may finally create incentives to rebuild herds, but any such recovery will take years.

Structural Weakness Meets Consumer Shifts

What makes the current price inflation so striking is that it is not caused by a short-term shock but by the slow collision of two long-term trends. On one side, cattle herds in major producing countries have been shrinking due to low returns, regulatory pressures, and alternative protein competition. On the other side, global consumption patterns have shifted in favor of precisely those parts of the animal that offer the least room for substitution. A striploin steak can be replaced by chicken breast in many households, but nothing replaces ground beef in a hamburger.

This dual dynamic explains why trimmings—the least glamorous component of the carcass—now command prices once reserved for prime cuts. And it explains why the problem cannot be solved quickly. Even if today’s high prices encourage more breeding, the biological lag in cattle cycles ensures that new supply will not hit the market until the late 2020s.

The Illusion of “Sudden” Price Spikes

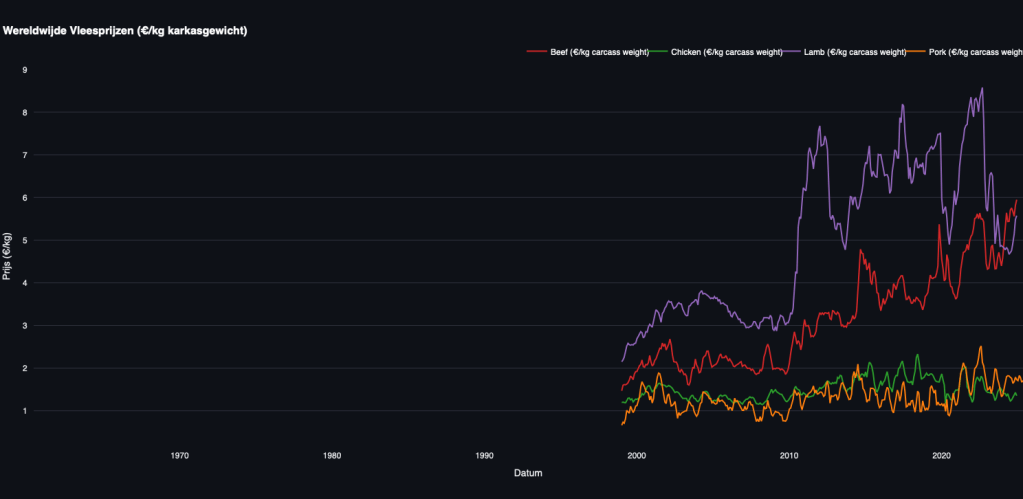

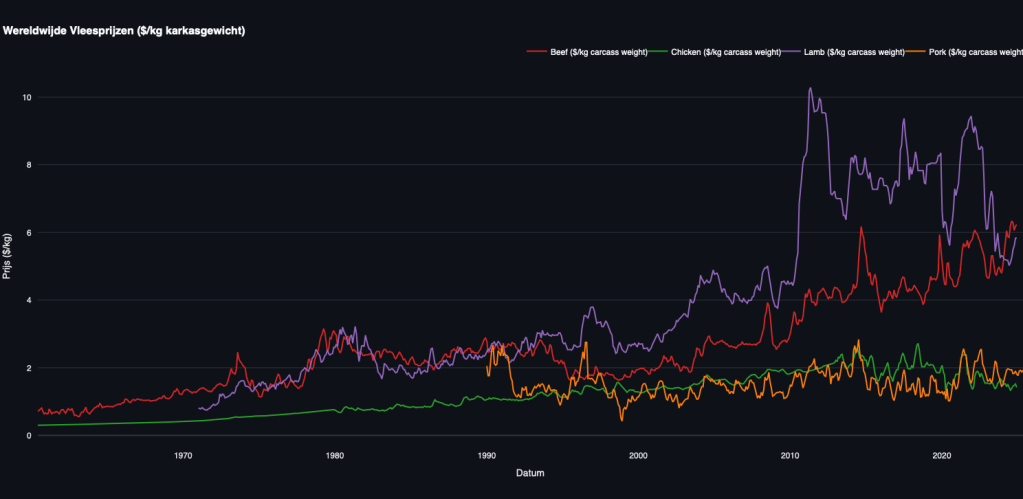

Consumers understandably perceive beef price hikes as sudden and dramatic. A package of ground beef that cost €6.00 a year ago might now retail at €9.00 or more. But the underlying trend has been visible for nearly two decades. Since 2004, U.S. slaughter cattle prices, measured by the Consumer Price Index, have been rising steadily. After 2010, the curve steepened noticeably. Since 2020, the index has more than doubled, culminating in today’s record levels.

Industry analysts have long warned of this outcome. In 2015, Rabobank published forecasts highlighting the structural imbalance between global demand and beef supply. Few policymakers paid attention. Producers were unwilling to expand herds without clear profitability, and consumers remained largely unaware of the brewing crisis because supermarkets and processors absorbed cost increases until margins were squeezed to breaking point.

Now, the reckoning is visible on store shelves. The notion that prices have risen “all of a sudden” is more perception than reality. The fuse was lit twenty years ago; it simply took this long for the explosion to reach the end consumer.

Beyond Conspiracies and Profiteering

Every time food prices rise sharply, suspicions surface about collusion, profiteering, or opportunistic margins among processors and retailers. The beef story is no exception. Social media fills quickly with accusations that supermarkets or distributors are “lining their pockets.” But in the beef trade, such claims do not stand up to scrutiny. Price fixing on a global commodity of this scale is not only illegal; it is practically impossible. The market is too fragmented, the trade too international, and the flows too volatile.

What we are witnessing is instead a raw supply-and-demand adjustment. Brokers are scouring the world from Botswana to Hungary for trimmings. Container loads shift hands at eye-watering prices. Importers outbid each other in search of volume. This is not collusion but competition at its most ruthless. The winners are those with the deepest pockets or the fastest logistics. The losers are consumers at the end of the chain.

The Future of Beef Pricing

What happens next depends on several factors, none of which suggest an imminent return to cheap beef. The first is herd rebuilding. Farmers in the U.S. and other major producing regions may now find cattle breeding profitable again, but any significant increase in herd size will take three to five years. The second is consumer behavior. If high prices trigger substitution—toward poultry, pork, or plant-based proteins—the pressure on trimmings could ease. But global demographic trends suggest demand will keep rising, particularly in developing economies where beef remains a status food.

Environmental and regulatory pressures add further complexity. Expanding cattle herds is politically and ecologically contentious due to greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and water consumption. Even if farmers are willing, policymakers may not be. That means the prospect of adding another hundred million cattle to the global system is uncertain at best.

The likeliest outcome is a prolonged period of elevated prices, with occasional dips but no sustained return to the low levels of the past two decades. Ground beef, once taken for granted as an affordable staple, is set to remain a premium product. For processors and retailers, this creates new challenges in product development, pricing strategy, and consumer communication. For consumers, it may mean rethinking how often beef is on the menu.

Lessons from a Slow-Burning Crisis

The story of rising beef prices offers a reminder that food systems change not in sudden shocks but in long cycles. When farmers underinvest for decades because returns are too low, the consequences only become visible years later. When consumers shift their preferences gradually toward different cuts, the cumulative effect reshapes entire markets.

In hindsight, the current situation was predictable. Analysts flagged the imbalance long ago. Meat traders noticed the creeping shift in carcass valorization. Observers like Wouter Klootwijk saw firsthand how prime cuts were quietly being ground into mince because trimmings were worth more. What seemed at the time like a marginal adjustment turned out to be a symptom of a deeper structural transformation.

As with many food system issues, the explanation is both simple and complex. Simple in that it boils down to supply and demand. Complex in that the drivers span decades, continents, and cultural habits. There is no villain to blame, no quick fix to apply. Only a recognition that the world has entered a new era for beef, where mince costs what steak used to, and where the true price of a hamburger reflects not just today’s scarcity but forty years of gradual change.

Leave a comment